My freshman year, a professor named Clint Tuttle dropped by the BHP Wednesday Seminar to talk about what he called “career drivers” – aspects of jobs like pay, projects, and culture – that determine how much we do/don’t like our work. Seeing as those thirty minutes gave me the best framework I’ve seen for job evaluation and answering the question “What do I want to do when I graduate?”, a post seems fitting.

The Drivers

While Clint’s original speech (as I remember it) only had six drivers, his current list contains eight [1]. The idea is that these eight aspects of any job are what we evaluate for any given position or role. We don’t really compare working at Google vs. Facebook, Tesla vs. Volvo, or Chipotle vs. In-N-Out; we compare the prestige or work-life balance or people or pay of these companies. Clint’s own descriptions and explanations for each driver can be found here. That being said, I’ve made a few changes to Clint’s list, and the set of drivers that I consider are (in no particular order):

Salary and Benefits

Work/Life Balance

Organizational Prestige

Social Impact / Deeper Meaning

People and Culture

What you Work on

Learning and Growth

Location

Compatibility with Future Goals

While it’s important to evaluate and compare jobs on a driver-by-driver basis, it’s equally important to consider how important that driver is for you. You shouldn’t tank your evaluation of a job with little-to-no organizational prestige if you don’t care about that. Likewise, if you don’t care about work/life balance but like the idea of future optionality, you should probably go into management consulting.

Salary and Benefits

Work pays the bills; a job that doesn’t pay enough to make ends meet is unlikely to be satisfactory, even if everything else is perfect. Nevertheless, study after study after study shows that above some income level (around $75,000 - 105,000), day-to-day happiness isn’t affected (though people’s opinions on their life continue to improve). Furthermore, think about how much happier you’d be earning $50,000 versus $500,000 versus $5,000,000. You won’t be 10x happier earning 10x more – though you’ll certainly be able to satisfy most/all of your desires at those three income levels. Thus, I always think about compensation through a logarithmic scale – exponential increases in earnings only translate to linear increases in happiness and satisfaction – and even then, only up to a certain point.

When evaluating the compensation structure, it’s important to consider the whole picture, not just the salary. For example, suppose you’re picking between two otherwise-identical jobs: one that pays $80,000 per year and provides $20,000 in non-taxable benefits (e.g. meals at work, a 401(k) plan, healthcare, etc.) while another pays a straight $100,000 per year without any benefits. Assuming that the benefits are all things you would have bought anyways, it makes more sense to go with the first option. You’ll probably save around $5,000 in taxes alone. Likewise, equity is also an important part of compensation. For smaller companies, however, equity can present extraordinarily uncommon opportunities – I’ll cover a personal example in a bit. On the flip side, equity can represent risk in compensation, and some people dislike that.

I view compensation levels as falling into one of five “buckets” that determine the amount of financial freedom available.

Jobs in the first bucket don’t pay enough to meet basic needs. This is the worst place to be.

Jobs in the second bucket can make ends meet, though there isn’t much disposable income to do things with. Nevertheless, you’re getting by.

Jobs in the third bucket enable various experiences – occasional weekend trips, eating out every now and then, doing cool stuff.

The fourth bucket is financial freedom – where you have the ability to do virtually whatever you want (within reason – you can’t fly to Paris for lunch or own an endangered species), and not worry about money. A vacation every year is completely doable, and you don’t really worry much about it.

The fifth bucket represents an earnings level where fully spending your earnings would necessitate waste.

So far, I’ve experienced buckets three and five. My internship at Akuna Capital placed me in the fifth bucket, and it’s not a good place to be. Money becomes irrelevant, and I started to waste it on things that didn’t matter. I spent $125 on a dinner, $200 at a nightclub (it was me and a friend, though that’s still hardly excusable), $400 on a gift for my cousins, and several hundreds on a phone. I stopped caring about prices and started rationalize them by saying “it’s only X minutes of salary”. Living life in the fifth bucket requires insane levels of discipline to avoid wasting it; it’s why lottery winners are more satisfied but not necessarily happier in the long-run.

Meanwhile, this summer’s internship is firmly in bucket three. I’m earning $15 an hour, paid 48% in cash (I need to earn the minimum wage of $7.25 for legal reasons) and 52% in equity – a rare arrangement for an internship. On the $7.25 an hour, given that my tuition and rent are functionally paid for, I can stretch out my earnings from this summer and what’s left of last summer to last me until my next internship. Nevertheless, I’m starting to see my bank balance dwindle as furnishing the apartment and other expenses take their toll.

A quick note on equity, and why I chose to receive it. My philosophy was that if the company does fail, then, at worst, I’ve just gotten paid a few thousand dollars less. Coupled with my habits of spending proportionally to the amount of money in the bank, this wasn’t a high cost. However, if the company did well (and, as an employee, I’ve seen firsthand how they’re doing), then my otherwise-insignificant pay would multiply substantially. To be fair, it’s a risky move that isn’t for everyone – taking on risk requires not only the stomach for it, but the financial stability in case things go wrong – but it’s one that I’m happy making.

Finally, a note of caution. I’ve found that because salary and benefits are so easily compared (after all, it’s just a number), I tend to overweight it over more qualitative drivers (e.g. people and culture) when it comes to decision-making time.

Update [07/22/2019]: This is a general phenomenon; people tend to focus on quantitative metrics because they’re easier to capture and compare than qualitative ones. Steven Kerr talks about this here.

Work/Life Balance

I feel like this driver includes two components. The first and most obvious one is the number of hours worked per week – it’s harder to work for 70 hours a week than it is to work 50. However, the variability and timing of those hours is equally important. Do you need to work on weekends? Do you need to start early in the morning, or work late at night? Are there days that you go home early, and days where you basically need a sleeping bag? Can you work on your own schedule, from wherever you choose, or are your hours more structured?

I’ve personally found that during school semesters, I can work most of the time, provided that I enjoy what I’m doing and that I consistently have a break – I aggressively allocate Saturdays for not-working time, and that’s usually all I need. However, during the summer, I’ve found that my motivation to do something productive after I come home from work is basically zero. As a result, more rigid schedules work better for me.

While I don’t care too more about work-life balance right now, I’d imagine that when I decide to start a family and settle down, it’ll rise much higher on my priority list.

Organizational Prestige

This one is fairly self-explanatory – it’s just how much prestige the organization’s name carries with it. Saying that you work for SpaceX or Tesla is sexy; no one really dreams about going to work for Independent Software Solutions Inc. or Unknown Austin Startup Inc. This is something that I try my best not to care about – though that can certainly require active effort at times. Much like choosing where to go to college, I find that prestige isn’t as important as fit along the other drivers.

Social Impact / Deeper Meaning

This driver asks two questions at its core:

How much of an impact are you having on the world?

How much meaning do you derive from your work?

Impact and Meaning is the reason that the non-profit sector exists – people want to do things bigger than themselves, and they want to effect change in the world around them. Certain companies do a better job here than others. SpaceX and Tesla attract talent that’s highly motivated to make humanity spacefaring and to accelerate the adoption of sustainable energy. Folks at Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods are working toward a better food system. Employees at Waymo and Cruise are trying to prevent 40,000 road deaths per year. Doctors and social workers are motivated by improving people’s lives. Impact doesn’t just mean how much impact you necessarily have, it can also apply at the company level. Accountants may not directly cure cancer or build a better car, but they certainly play a crucial role on the team that does.

I’m starting to realize just how important this driver is for me. I used to watch crash test videos of Volvos and stare in shock and awe at how well-engineered their vehicles were. The safety engineers that work at Volvo are first-rate; the number of innovations they’ve created (e.g. the seat belt) have saved literally thousands of lives. This is what it means to have an impact on the world, this is what improving people’s lives means. The meaning that they must derive from their work (I’d wager) is huge.

While it’s possible to fold this into the “What you work on” category, I think it merits its own section because of how broad the category would be otherwise.

People and Culture

People and Culture is about how well you get along with those you regularly interact with. People you interact with can involve not just your coworkers, but also customers and employees of other companies. If you’re not a people person, maybe don’t go into sales – even if you love your coworkers.

A solid proxy is to ask yourself if you’d spend time with people associated with work outside of work – if the answer is a resounding no, that’s a bad sign. The other component to this driver, workplace culture, is hard to describe, but ultimately the acid test that I use is to consider whether you feel comfortable in your workplace.

While a mediocre or non-existent/weak culture can’t actively do damage, great company culture can go a long way for happiness, and actively bad culture can do the same. It’s also worth pointing out that some people (e.g. me during the summer of 2018) don’t care much about diversity until they’re in an environment without it. While I was interning at Akuna, the gender ratio among full-time traders was infinite – there were probably 60 or so full-time traders, and none of them were female. At my current internship, virtually everyone in the office is fairly introverted, though I’m not. Ultimately, I wouldn’t want to spend extra time with most of my co-workers outside of work.

[Update, Nov. 4, 2019: I think it’s also worth adding onto the people dimension something related to how smart your co-workers are. In general, the personalities and traits of your co-workers in an important factor to consider.]

What you Work on

What you work on is all about the projects and tasks that are a core part of your role. Here, it’s important to consider both the day-to-day tasks and the bigger picture. Data analytics roles can involve a fair amount of menial labor (especially during startup phase), but the work can be incredibly interesting (to some people). Options traders’ day-to-day is relatively bland in comparison to the few days and minutes a year where markets really start to move. Again, an easy proxy exists for this category: would you want to work on your job’s projects and tasks outside of work?

I put recognition into this category, as I think it fits best here and didn’t want to break it out into its own driver. The relevant questions are: Are you recognized for your contributions to the company? If so, is that recognition meaningful or just a token? Is it often, or infrequent? While I don’t think I’m motivated too much by recognition, it’s a very crucial tool for motivating some types of people.

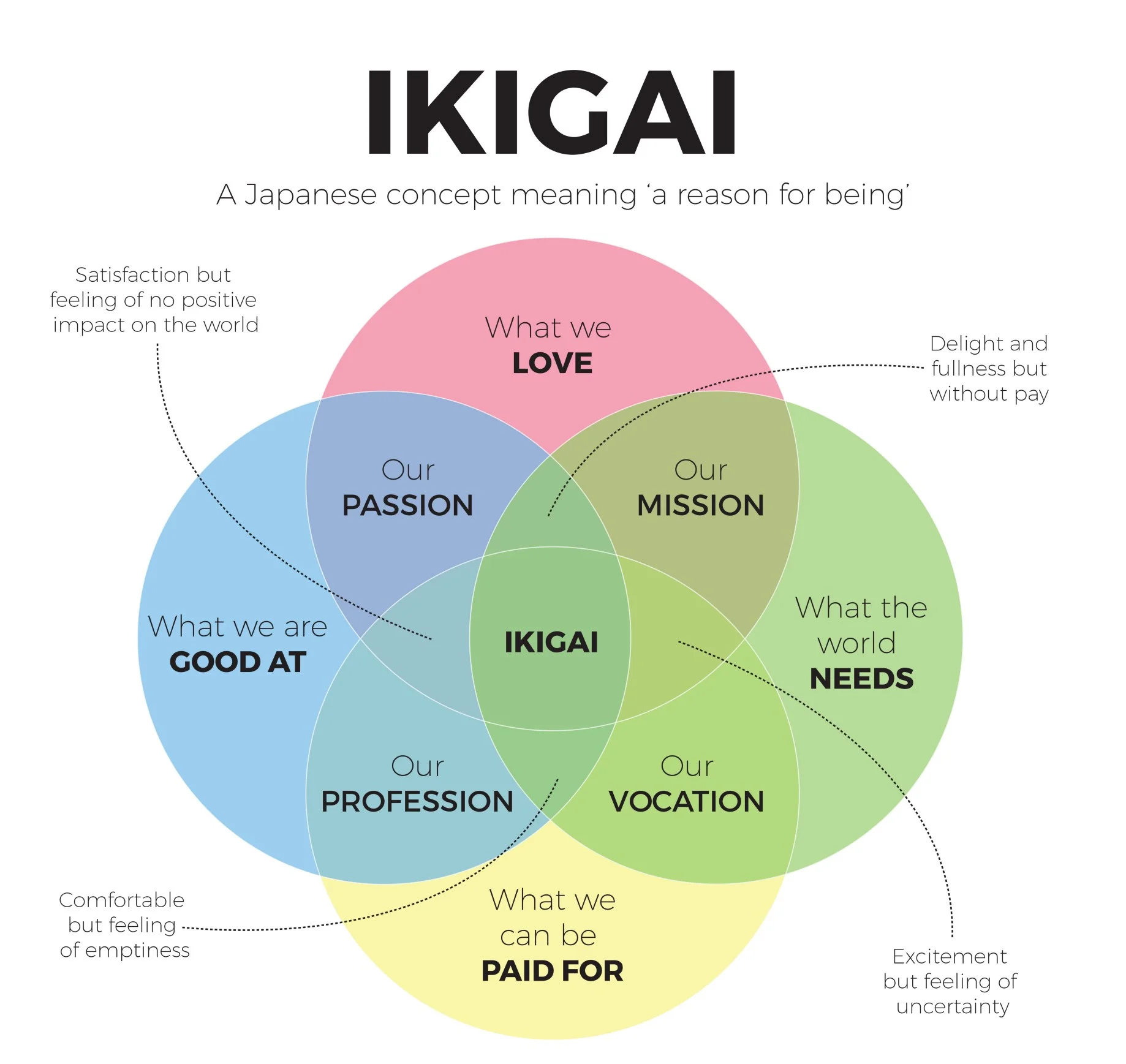

The Japanese concept of Ikigai is highly relevant here. What you work on should be (1) profitable, (2) something you’re good at, (3) something you’re interested in, and (4) something that fulfills a need for the world.

Learning and Growth

Learning and Growth is about becoming a better person, professionally and personally. Consider your strengths – are you good at what you do? If you aren’t, does the job provide the support and time to enable you to become better at it? Does your job enable you to meet other people in the field (both at and above your pay-grade) and develop relationships? Can you build your skills to prepare yourself for whatever comes next?

Especially for internships, this category also encompasses the questions of “To what extent do you learn more about the industry?”, “To what extent do you meet new people?”, and “To what extent do you learn about your drivers?”. Internships ought to be learning opportunities; an internship where you learn nothing about the job, the industry, or yourself has an upper limit of how useful it is.

Your boss has a lot of influence here (along with “What you Work on” and “People and Culture”). Is your boss actively involved in your development?

Location

Location is more than just what city you’re in. Is the company in a nicer or worse part of that city? What’s near the office? Is travel ever necessary to meet relevant parties – how often? My experience with talking with ex-consultants is that traveling is fun and exciting in the beginning, until it loses its luster. Some things to consider here are state taxes, the weather, and distance to family and friends – along with the ease with which you can meet new people outside of work.

Compatibility with Future Goals

This is the last driver on the list, but it’s a big one for me. The core question is: How well does the current role tie into what you might want to do in the future? As an example, management consultants have the opportunity to work abroad, go to business school, get promoted, or leave for another job – there’s a high amount of optionality post-consulting. As a result, if you aren’t 100% sure what you might want to do, consulting is incredibly helpful at figuring out your future goals. If your goal is to become CFO for a company, you probably shouldn’t be a software engineer; it doesn’t further that goal.

Tieing into this, promotions are basically future job options, so this driver also encompasses the ease with which you can add to your list of rights and responsibilities.

Prioritizing Drivers

There’s no formal process for ranking the drivers. Rather, some priorities can be set with a fair amount of introspection and thought. However, it’s worth being aware of the effects of psychological biases, especially availability. We tend to overweight recent experiences over older ones, so things we did or didn’t like about our previous job will tend to rank higher to preserve/avoid those experiences.

As another resource, the official Drivers Exercise website can be found here, and a video of Clint talking through each of his eight drivers can be found here. Data on other people’s priorities can be found here. Don’t match your priorities to other people’s, though it can be interesting to see how you do/don’t align with others in your preferences.

[1] Clint talks about travel and risk in the FAQs that immediately follow his descriptions, but ultimately decides on 8 drivers.